Finding Home: 30 Years In The Making

- fiorella

- Feb 25, 2025

- 20 min read

Updated: Feb 27, 2025

Prologue

Por siempre mi voz oirás y al mundo descubrirás.

Each time someone asks where we're from, we pause. It’s a simple question on the surface. The answer is anything but. Do they mean where we were born? Where we grew up? Where we live now? Or are they asking something deeper—where our hearts feel most at home?

We could say Mexico, and that would be true. It’s where our story began, where our roots run deep, where family gatherings are loud, and the scent of freshly made tortillas lingers in the air. It’s where we first learned to walk, to talk, to dream. It’s the place that shaped us before we even knew we would leave.

We could say Canada, and that would be true too. It’s where we grew into who we are today, where we built a life from scratch, where we carved out a space in a country that wasn’t always familiar but slowly became home.

Or maybe the answer is somewhere in between. Maybe we are from the airports that have carried us back and forth, from the tearful goodbyes and the joyful reunions. Maybe we are from the in-between spaces, the pauses before answering, the moments when we have to gauge what version of our story the person in front of us is really asking for.

Because home isn’t a singular place for us—it’s a collection of memories, of people, of languages, of smells and sounds that don’t belong to just one country. It’s a mix of traditions and inside jokes, of childhood nostalgia in one place and adult realities in another.

So when someone asks, where are you from? we pause. Not because we don’t know the answer, but because there isn’t just one.

Chapter 1

A donde el corazón se inclina, el pie camina.

Every immigrant story begins with a dream. For T, that dream was sparked by a high school friend’s mom who waxed poetic about the land of maple syrup. Mom, on the other hand, had a path laid out in Mexico. Her father ran a booming import-export business, and staying put was the sensible choice. But love has a way of throwing practicality out the window—along with Mom, who suddenly found herself knee-deep in snow.

As newlyweds in the 80s, they moved to Toronto on T's student visa but wound up spending several months braving a Nova Scotia winter. Somewhere between shoveling snow and wondering if their toes would ever thaw, they decided Canada was the place to raise a family. They returned to Mexico and began the bureaucratic circus of securing residency. It was a process that spanned years and tested their patience at every turn. But they never gave up—because giving up, as they’d discover, wasn’t in their DNA.

Having grown up in Mexico City, by the 90s, Mom and T were living in Veracruz with their two young daughters, Fiorella and Anarella (but you can call us Fio and Ana). Mom taught hospitality at a local university, while T worked as a civil engineer. We had a live-in nanny and attended private school—on paper, it all seemed ideal. But Mom was locked in a daily battle with the local wildlife—flying cockroaches. These winged nightmares had a knack for showing up uninvited, like tiny helicopters of terror, and she loathed every single one of them. The heat didn’t help either, turning every day into a sweat-stained ordeal that she calls la antesala del infierno.

T had his own grievances, fed up with the corruption that seemed to ooze into every corner of life in Mexico. So when they won the visa lottery, they rolled the dice on a better future.

At the time, no one in their families lived outside of Mexico. Immigration felt like a grand adventure into the unknown, full of uncertainty and leaps of faith.

Ana and I had traveled to the U.S. before—skiing in Texas (yes, Texas) and chasing Goofy around Disneyland. If nothing else, we had memorized the lyrics to "It's a Small World After All," which, in hindsight, was a hilariously ironic anthem for the journey we were about to undertake.

Just months before the big move, the Mexican Peso was devalued, cutting Mom and T’s hard-earned savings in half. Undeterred, they packed up their dreams, fears, and now-diminished savings, determined to turn every peso into a fresh start.

Chapter 2

Contigo la milpa es rancho y el atole champurrado.

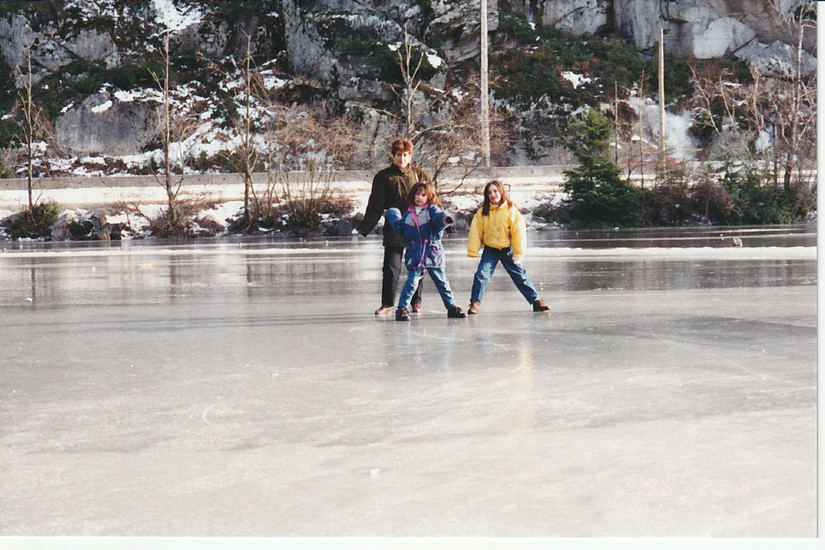

T flew solo to Canada on New Year's Eve 1994. Armed with hope, limited English, and a whole lot of courage, he landed in North Vancouver and rented a room from a German couple, Melina and Frank. Shortly thereafter, he secured a basement rental off Fern Street—complete with a cat named Patches. With a home in place, it was finally time to join him and start a new adventure together.

In April 1995, we arrived with a few suitcases and the kind of blind optimism that only immigrants and lottery winners possess. We had no roadmap, no Google, and no clue what awaited us—only a dream, a deep stubbornness, and an unshakable belief that we could make this new place home.

Stepping off the plane, we were instantly bewildered. In Mexico, homes were hidden behind tall fences, armed soldiers patrolled the streets, and guards stood watch outside fancy stores and banks. The streets buzzed with Volkswagen taxis, honking cars, and the hollers of construction workers offering unsolicited fashion advice to passersby.

Vancouver, on the other hand, felt like stepping into a parallel universe. There were open yards, trees bursting with squirrels, snowcapped mountains, and rocky beaches. Dog parks and even dog bakeries were a thing—along with dog owners dutifully cleaning up after their pets, a stark contrast to Mexico’s blissful disregard for poop-related responsibilities. The streets were so quiet it was almost eerie. Mom couldn’t help but wonder: How on earth was she supposed to know if she looked good, ask Patches?

At 5 and 8 years old, Ana and I joined kindergarten and grade 2. We attended ESL classes with classmates from Japan, Taiwan, Poland, and Thailand, tackling English together one word at a time. But at home, Mom and T insisted on a strict Spanish-only rule, refusing to let the pressure to assimilate erase our heritage. It wasn’t easy, especially for two young girls eager to fit in, but looking back, it was worth it.

T became a mailman, and the job quickly turned into a family affair. Evenings were spent sitting on the floor together, stacking piles of flyers, and mornings began before dawn as we headed out to deliver them in West Vancouver. Mom found her own way to contribute, baking scones for a restaurant at Park Royal, her kitchen filling with the warm, comforting scent of baked goods.

Back then, there weren’t many Latinos in Vancouver. NAFTA had only been enacted in 1994, so immigration was still a slow trickle, and adjusting to Canadian life came with challenges both big and small. Opening a bank account turned into a philosophical debate: why was our last name supposed to be just one word? Were Mexicans supposed to celebrate Cinco de Mayo? Why were beans and corn sweet, and why on earth was cream sour?

Our new beginning was not without heartbreak. Just weeks after our move, Nonna passed away, leaving a void that no distance could soften. Through the tears, we told ourselves that rough starts build character—and began learning, as a family, just how strong we could be.

In a string of events that became a source of much-needed comic relief, Mom repeatedly failed her driving test. In Mexico, stop signs were more of a suggestion, so adjusting to Canada’s rigid traffic rules was—let’s say—a creative challenge for Mom. The punch line? Mom now drives a public transit bus. Yes, the same woman is often behind the biggest wheels on the road.

While Mom figured out exactly where to stop and for how long, we hoofed it to the grocery store with admirable determination. Our go-to route included a shortcut that involved skipping stones across a river—a strategy that worked beautifully on the way to the store but became a questionable life choice when lugging groceries home. More than once, we found ourselves chasing a rogue loaf downstream in a dramatic dinner rescue mission.

We discovered a small church on a Squamish reservation in North Vancouver, where a weekly mass celebrated in Spanish brought out immigrants from Mexico to Chile and Argentina—a cherished connection to home.

Our first Christmas in Canada was simple and magical—because it was entirely our own.

Unlike past Christmases, Nonna wasn't there to spoil us with trips to Toys “R” Us, and Mom and T had pushed themselves to the brink juggling new beginnings in an unfamiliar world. But they never wavered in their commitment to making our first Christmas special.

Mom painstakingly recreated the food we loved, determined to bring the familiar tastes of home into our tiny kitchen, even if she had to hunt through multiple grocery stores to find the right ingredients. We decorated a tree with a homemade popcorn garland. We used candy canes and chocolates as ornaments. And Santa—who, like everyone else that year, was on a strict budget—delivered gently used toys. There was no large fireplace like the one we had in Mexico, but there was real snow—soft, silent, blanketing the world outside like something out of a movie.

Chapter 3

Haciendo y deshaciendo se va aprendiendo.

Life was a mosaic of firsts with their own challenges, surprises, and lessons—some hilarious, others unexpected. There were our first bruised tailbones following encounters with black ice. Our first Jack-O-Lanterns and our first Easter egg hunt. Having never encountered the Easter Bunny, Mom was caught completely off guard when we woke up brimming with excitement. With no eggs, no candy, and no plan, she improvised. As we eagerly searched the house for clues, Mom slipped away and hastily hid whatever she could find—a few stray liquor-filled chocolates Nonno had left behind. That Easter, Mom’s quick thinking turned chaos into a treasured memory—proof of the resourcefulness that would guide her through every challenge in our new life.

Of course, there were also Mexican traditions we missed like 16 de Septiembre, Dia de los Muertos, and Los Reyes Magos. I can’t count the number of Dolly Pockets mom sacrificed to her endless attempts at baking roscas. They were delicious but my half-melted, flat-faced Dollys never could successfully live up to the role of baby Jesus.

Thankfully, Nonno quickly started a beloved tradition: spoiling Ana and me with roundtrip airfare to Mexico City each summer. With airline VIP badges proudly pinned to our clothes, Little Fio and Little Ana became seasoned travelers, bravely navigating the skies on our own. Back in Mexico, we were known as the Canadian cousins, a title that brought a mix of intrigue and pride. Our relatives lined up to host us, ensuring every visit was filled with love, laughter, and enough tacos al pastor to last a lifetime.

Mom and T stayed behind, working and awaiting our return, if nothing else for our suitcases which were bursting with treasures: tamarind candy, canned Oaxaca cheese, and a bottle or two of sambuca liqueur that should've raised a few eyebrows at customs. These trips became more than a summer vacation—they were a lifeline to the family and culture we had left behind, filling our hearts and our pantry with the flavors of home.

Chapter 4

Así se lleva a México en la piel.

Our family eventually moved out of the basement and into an apartment right across from a hospital. It wasn’t perfect—far from it. The tenants upstairs were the loudest walkers imaginable, prompting Mom and T to perfect their ceiling-banging broom routine, the universal “quiet down!” signal. And then there were the ever-present sirens, a feature of our new location that even the broom couldn’t fix. But the building had a pool, and that alone made up for all of its flaws.

We embraced new school traditions like Outdoor School and visits to the Long House—experiences that would have been unimaginable in a Mexican curriculum. Meanwhile, Mom and T scratched their heads over Canada’s obsession with Tylenol. Was Mexico overprescribing antibiotics? Sure. But at least antibiotics felt like they could go to battle with the flu.

Friendships blossomed but T was perpetually baffled—and annoyed—by what he perceived as our friends’ rudeness. Unlike the warm Mexican greetings he'd always known, when our friends came over, they never said hello, an act that violated every rule of basic courtesy (though Canadian families simply didn’t see it the same way).

Perhaps that’s why Mom and T sought out a slice of Mexico in Vancouver. The Hidalgos had arrived in Canada a year before us and were eager to share their hard-earned wisdom. Mela and Esteban’s jokes were legendary, and Pera’s artwork adorned the walls of every family gathering. Coco and Vicente added their own warmth to the growing community. And Vero was famous for her birthday song and dance (and the only cajeta ice cream cake I’ll eat).

In our chosen family of fellow immigrants, we found proof that home could exist wherever love, culture, and community flourished. By the time our family moved into our first house in 1997, we had a village.

Mela, Pera, and Mom signed us kids up for catechism at St. Edmund’s, ostensibly to maintain appearances for their families back in Mexico. But, truthfully, it was a brilliant excuse for a night off. Thursday nights became sacred—not for the prayers, but for the impromptu adult therapy sessions that unfolded at the local pub. As we memorized Hail Marys and wrestled with the mysteries of the bible, our parents traded laughter, vented frustrations, and leaned on each other for support.

Those pub nights were filled with stories of triumphs, struggles, and hilarious cultural missteps. And they routinely lost track of time. We were often the last ones waiting in the parking lot, nervously glancing at the annoyed church staff who inevitably asked, ”Where are your parents?”

After countless laughs and shared memories, Vicente, Coco, Pera, Mela, and Esteban moved their families back to Mexico. Life in Canada was challenging, and the familiarity of home beckoned. Mexico offered the comforts of family and ease that Canada often lacked. Still, their visits back to Vancouver—and the bonds they left behind—remind T and Mom that they are never alone.

Only a few families from the original 90s crew remain. But with the new century came new friendships, not to mention Canadian citizenship! The Bobadillas arrived in 2000, soon followed by the Rojas. Friendships were cemented on summer camping trips, where late-night s’mores and stories by the fire turned acquaintances into family.

Chapter 5

El que quiere azul celeste, que le cueste.

Our journey was anything but linear as Mom and T took odd jobs to make ends meet. Mom baked banana bread for a café at Lonsdale Quay, cleaned homes, and eventually established a small business bringing international students to Canada to study English.

Somewhere in Mom’s drawer, there’s probably still origami paper and chopsticks gifted by Chie and Tetsuya from Japan. Then there were the students from Korea, who introduced the family to kimchi—it sure took these Mexicans a while to get used to pickled cabbage in the fridge. The Brazilians brought energy and warmth—and comedy as T tried to talk to them in Spanish, with mixed results.

T was famous for never remembering anyone’s name. Having grown up in a homogenous city, he’d never been exposed to other cultures and often mixed them up. Luckily, there were also plenty of students from Mexico, like Liliana, whose recipe for shampoo lives on in Mom’s shower. Thanks to Mom, our home became a hub of global exchange—and life lessons.

T wore many hats over the years, each one more colorful than the last. He installed sprinklers, organized garages, and worked at the Mexican Consulate, but his claim to fame was being a film extra. He appeared in countless movies and shows, including The X-Files, Medusa, and Double Jeopardy. His favorites, though, were the Westerns. He could play a dead soldier or an alien as well as the next guy but in his heart, he was always a cowboy. And he'd sign any waiver they handed him if it meant he could ride a horse.

For years, he worked night shifts at 7-Eleven. His job came with free Slurpees for us—an obvious perk. The night shifts, however, meant the entire family had to master the art of moving through the house like ninjas, a skill that came with a lot of trial, error, and dropped pans. To supplement, T took seasonal work at IKEA. There were even times when he found himself driving from one job to the other, switching uniforms at red lights. At their As Is department, he honed furniture assembly skills that are in demand to this day.

Mom spent years in retail, working at both Bombay, where she nurtured her passion for home décor, and Reitmans, where her wardrobe flourished along with her friendships. At one point, she even ran a home daycare. Suffice to say our parents weren’t bored. And if multitasking were an Olympic sport, our home would be filled with gold medals.

After hundreds of infuriating rejection letters for being "overqualified," dozens of interviews, and countless failed professional ethics tests—learning to speak English is one thing, learning to speak ethics is another—T finally landed his first job as an engineer.

The job itself was nothing short of an adventure. T was flown by helicopter into remote northern B.C. communities, where, after checking for grizzlies, he’d be dropped off for hours to record measurements and conduct maintenance at 575 meteorological stations. Out there, surrounded by rivers, trees, and the occasional bear track, he was in his element. But the job didn’t last long. When funding ran dry, T found himself pivoting yet again, this time as a bus driver for TransLink.

Watching Mom and T do whatever it took to keep us afloat, no job too small, no shift too inconvenient, left an impression on us. It’s why we never make excuses at work, why we’re team players, and why we’re not too proud to roll up our sleeves when needed. They showed us that no job is beneath you if it helps move you forward towards your goals.

Chapter 6

Del plato a la boca se cae la sopa.

Somewhere along the way, we rescued a lucky black cat named Séuz from a garage sale. He joined the family, along with a string of unlucky birds. Cockatiels became too expensive to replace, so we switched to budgies—blue Dixies and yellow Panchos came and went, much to Séuz’s delight.

Living off Grand Boulevard gave T and Mom a front-row seat to Sutherland High School and its parade of mischievous teenagers. They witnessed the seasonal bomb threats timed around exams, the rainbow-colored hair, goths, and kids with enough piercings to set off a metal detector—none of which were common sights in Mexico at the time. During a tour of the school, the principal, in what seemed like an attempt to reassure parents, proudly pointed out the designated spot where kids smoked weed and the onsite daycare for pregnant teens. Our fates were sealed.

We donned knee-high socks and kilts at Saint Thomas Aquinas, a former convent turned Catholic school. Mom took on volunteering at the school’s bingo nights and made church offerings to help offset the cost of tuition. We found new best friends and shared plenty of band camps.

Meanwhile, Mom and T took a brief detour into managing a small cash loan business with friends. That venture fizzled out quickly. Thankfully, brighter days followed. T passed his ethics test, joined the association of professional engineers, and managed to leverage his bus driving gig into an engineering role at Coast Mountain Bus Company. Hallelujah—it was a win the whole family could celebrate.

Since TransLink had been a solid job for T with good pay, great benefits, a pension, and a union, it only made sense for Mom to join too. After completing her training, Mom became a bus driver—a fact that required some creative spin when explaining it to relatives in Mexico, where public transportation still carries certain social stigmas. While her sisters were busy perfecting their casserole recipes, Mom was expertly maneuvering a 40,000-pound bus down icy hills, dodging unpredictable drivers, and dealing with passengers who brought their life stories (and sometimes their lunch) along for the ride.

On more than one occasion, she picked up Chinese tourists, complete with suitcases, who eagerly boarded the bus to Victoria Drive—because, naturally, the sign simply said Victoria. It was a few stops later that they realized the Victoria they were looking for was on Vancouver Island. Can’t really blame them for being confused, but Mom still had to break the news that her route, impressive as it was, did not include a ferry crossing.

That brings us to 2005. Ten years after arriving in Vancouver, our family bought our first home.

Chapter 7

De tal palo, tal astilla.

Just as before, our door was always open.

Our family grew to include two beloved and loyal feline companions, Tomás and Lulú. And our chosen family continued to expand.

For us, the true gifts our parents bestowed through immigration became clearer with time. The physical contrasts between Canada and Mexico—the landscapes, the climate—faded in importance. What stood out more were the philosophical differences. On a visit to Mexico, we learned our cousin had been ostracized for being gay, a painful reminder of the lingering stigma around sexuality. Street dogs roamed neighborhoods, while pet dogs were often confined to chains. Classism dictated social circles, shaping who our relatives associated with, and gender roles placed strict limits on what women could aspire to or achieve.

These cultural divides, once subtle, became harder to ignore as we grew older. Returning to Mexico brought both joy and sadness, a bittersweet love for our roots tempered by frustration with these realities. Yet, in recent years, the progress has been undeniable. The country has made huge strides, offering hope that the Mexico we cherish continues to evolve.

By 2010, our family began to forge our own paths, each driven by a shared desire to broaden our horizons and explore new worlds. I unsurprisingly pursued international development. Ana surprisingly pursued international tax law. And we were bit by an irrecoverable case of the travel bug.

Life, of course, had its twists. Mom and T eventually went their separate ways. Mom moved to Pitt Meadows and is still the only of five siblings to have ever bought her own home. Dad found home in the foothills of Burnaby Mountain where he can escape into the forested trails at a whim. Ana moved to Uganda and I moved to Japan.

As one of the few mzungus in the town of Mbarara, Ana ventured confidently into the market on a mission to buy chicken. Expecting the familiar sight of neatly saran-wrapped packages, she was instead directed toward a row of live, clucking chickens. Confused but determined, she attempted to clarify—she wanted chicken for dinner.

So, they killed a chicken.

Realizing the misunderstanding but still hopeful, she tried again: she needed it ready to cook. Without missing a beat, they deplumed it. And just like that, she found herself holding a bag of still-warm, freshly butchered chicken. It looked nothing like the chicken at the grocery store and it made for an unforgettable lesson in where our food comes from.

Meanwhile in Japan, after triumphantly translating the kanji for milk, I proudly bought it every week, only to discover—a full year later—that I’d been buying banana milk the whole time. It wasn’t until Mom visited and asked why her coffee tasted like bananas that I noticed. To me, it hadn’t tasted like bananas—it had tasted like success.

In 2014, our family reunited when Mom was diagnosed with breast cancer. Still reeling from a double mastectomy, Mom's doctor suggested she host a funeral to grieve her old boobs. Mom flipped the script and threw a party for the new ones instead. We learned to bake C cups and decorate the most elegant buttercream icing sprinkle-covered bra cake the world had ever seen.

Mom’s recovery, besides a triumph of Canadian healthcare, reminded us of the strength we drew from one another before we inevitably dispersed again, ready to tackle new adventures.

Ana moved to the Netherlands and then Panama, and I moved to California. Mom and T supported each other in our absence, even learning to travel together to see us. They made new friends and cherished old friends. Mom found a love for books and T began learning Italian. The bonds we shared and the annual family adventures to new corners of the world kept us connected, no matter the distance.

Chapter 8

Lo que bien se aprende nunca se olvida.

Just like that, we've arrived at 2025. We’ve weathered storms both together and apart, emerging stronger with every twist and turn. Following the pandemic, Ana settled on Vancouver Island and I in Vancouver, Washington. As Mom and T approach retirement, they’re facing a chapter that promises to look nothing like the one they might have imagined in their youth—but knowing them, it’ll be filled with reinvention, and maybe even a few surprises.

Some Canadian habits have become second nature. Ana sends out party invitations with an end time. T can’t go a day without his English Breakfast Tea. He'll scold anyone who fails to properly sort the trash. And heaven help the soul who enters mom's house without taking their shoes off. Indoor voices only in the hallway. Recent photos of black bears? Always on hand. Mom and T have even embraced their 4-legged grandchildren with open arms buying Basil ice cream for his birthday and mastering the art of putting pajamas on Xóchitl. Is our Canadian transformation complete?

Not a chance. Tacos are still our love language. Tajín is a pantry staple in all four households and Ana carries Valentina in her purse, por si las moscas. We know every word to Timbiriche and wouldn’t be caught dead swimming in cold water. We’ve got moves on the dance floor, not like the aguados, and we top off most meals with avocado. We’ve become cultural mutts—blending traditions, quirks, and languages, we’ve built an identity that’s uniquely ours: resilient, curious, and a little spicy.

Mom and T’s accents persist, a poignant reminder that as long as we’ve been in Canada, a part of us remains foreign. No matter how many years have passed, their accents carry the weight of where they came from. It lingers in the rolled R’s that slip into their words, in the slightly musical lilt of their sentences.

Their accents are more than just speech patterns; they are living proof of the lives they had before Canada, and the culture they carried with them. Proof that you don’t have to lose where you came from to belong somewhere new. They are the soundtrack of our home, where Spanish slips effortlessly between English, where dios mio and vale gorro punctuate conversations about everything from taxes to lost car keys.

They are also a quiet reminder of how the world sees them. Because no matter how Canadian they have become—no matter how many winters they’ve endured, how many hockey games they’ve sat through—there are moments when their accents give them away.

For us, their accents are a comfort, a tether to something deeper. They remind us that while we have grown up straddling two cultures, while we may not have accents ourselves, we are still part of that story. They remind us that no matter how much time has passed, a piece of us will always be from somewhere else. And that’s something we wouldn’t change for the world.

Chapter 9

Cada quien cosecha lo que siembra.

In many ways, immigration has gotten easier. Vancouver now boasts tortilla factories, and Spanish feels almost as common as maple syrup. Need to rush back to Mexico? Multiple daily flights make it effortless, and video calls keep family just a screen away.

Mexico is no longer reduced to burros and sombreros in people’s minds. Libraries stock books in Spanish, and streaming platforms offer Spanish subtitles—small but meaningful steps that bridge the gap for newcomers.

The resources available today would have felt like pure science fiction back in the ’90s. For families like ours, it’s a reminder of just how far the world—and its welcome mats—have come.

And yet, it’s an odd time to celebrate immigration. Around the world, governments are tightening their borders, enacting increasingly isolationist policies.

We get it. We even saw it coming.

Could Mom and T have overstayed their visa back in the ’80s? Easily. Could we have been born in Canada, securing an automatic shortcut to citizenship? Yup. Could we have claimed proximity to violent drug wars as an entitlement to a better life? Just as much as the next family.

But we never did.

Mom and T never risked deportation, never risked our family being separated. They never put us in a position where we couldn’t return to visit the people and places we came from. They never wanted us to learn that shortcuts were the way forward. They never wanted us to believe we were owed anything beyond what we earned.

T since spent years calling city halls in Tuscany, sorting through generations of birth certificates to secure Italian citizenship. I since submitted hundreds of pages of documents, took civic tests, English tests, and even a tuberculosis test to earn American citizenship. And as immigrants several times over, here’s where our views differ from the ones folks often expect.

People who cheat suck. And let’s be honest—immigration fraud is rarely a one-time offense. It’s not just about bending the rules to cross a border; it’s a pattern of entitlement, of believing rules don’t apply to you. The ones who cut corners aren’t just affecting their own fate—they are why some people assume every immigrant is here to take something instead of build something. They fan the flames of racism and make things harder for everyone else.

So stand against illegal immigration. We stand against it too. But don’t lump all immigrants together. Because legal immigration is an admirable thing.

Immigration is a mosaic—countless unique pieces coming together to create something greater than the sum of its parts. It is the blending of languages, traditions, and perspectives that challenge us to think differently, to grow beyond what we know, and to see the world through a wider lens. It is the flavors of different cuisines, the rhythms of different music, the wisdom carried through generations of stories, and the innovation that comes from people with different lived experiences working toward a common goal.

The first taste of wasabi, which looks like guacamole but delivers a fiery surprise. The first time seeing someone wear a turban. The first sky-bound lantern wish at a Lunar New Year celebration. The first real taste of the rest of the world at your doorstep. That’s what immigration should be about.

It sparks curiosity. It fosters empathy and understanding, breaking down walls of ignorance and fear. And it’s not something to be tolerated—it’s something to be celebrated.

So on our 30th anniversary, we celebrate the immigrant spirit: the ability to adapt, to persevere, and to find joy in the unfamiliar.

Chapter 10

Caminante, no hay camino, se hace camino al andar.

Too often Ana and I took for granted the unspoken fears and immense effort behind each step forward. The sacrifices that felt invisible at the time were all acts of love, quiet and unwavering, in pursuit of a dream.

Our journey is about friends who became family and a country that became home. But most of all, it’s a story of gratitude—gratitude for the opportunities Canada offered, for the twists and turns that shaped us, and for the memories that bind us, 30 years in the making.

The cost was high, but the rewards immeasurable. And none of it would have been possible without the strength and determination of Mom and T.

Who we are is a testament to two people who never lost sight of their dream.

Mom and T,

We’re not only grateful—we’re profoundly proud.

The lessons instilled are something we'll carry forward forever. Because immigration doesn’t just change where you live—it changes how you see the world.

Comments